In fact, it was

downright crooked

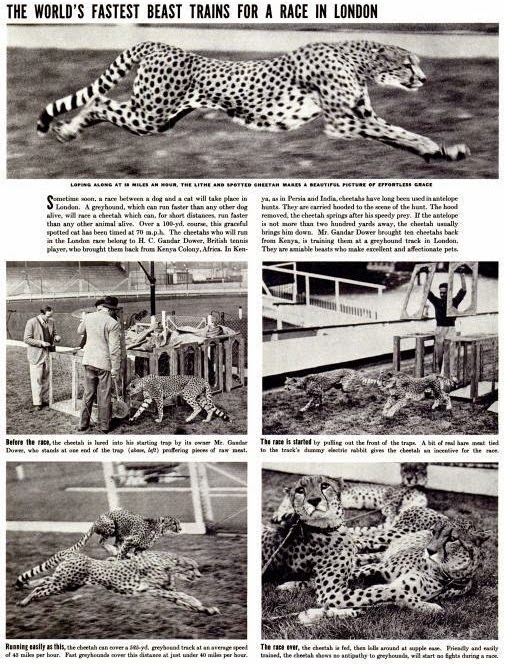

Note that "Burlingame Telegraphing Typewriter" has been superimposed on this engraving. In reality, it never appeared on any device.

Burlingame's "invention" was actually based on Adolph Schaar's Tel-Autoprint.

This booklet was part of the promotional campaign launched in California in 1908 for the highly-fraudulent Burlingame telegraphing typewriter enterprise. The contents came nowhere telling the truth about Burlingame and his fake machine. The real invention, by Adolph Schaar of Oakland, California, was illegally acquired in the first place. Robert Cleveland was commissioned to write and put his name to this nonsense.

Elmer Allah Burlingame did prove his ability to transmit words from one place to another, in LaPorte, Indiana, as early as November 29, 1903. He was "pronounced to be of the devil", but he didn't use a telegraphing typewriter for this purpose:

By the genius of Elmer Burlingame, a LaPorte boy, the sermon preached Sunday by the Reverend Dr D. H. Cooper, pastor of the First Baptist Church, at Peru, was heard in Logansport, Wabash, and by dozens of people in Peru. Previous to the meeting no announcement of the innovation was made. A transmitter was placed in front of the pulpit and connected with the Home Telephone Company's exchange, where Burlingame was waiting to ascertain the success of the experiment. When it was learned that the arrangement was working satisfactorily, friends in Peru and other cities were called up. It is said that the clergy are alarmed at this but they need not be. They fear that such inventions will increase the habit of non-church-going which is already so prevalent. But there is a power of sacrament and an atmosphere of worship which cannot be transmitted over telephone wires, and which can be received only by one's personal presence in the congregation, and this will come to be understood.

- LaPorte Argus-Bulletin, December 2, 1903

And the telegraphing typewriter he took from San Francisco back to LaPorte five years later was far from being entirely his own work.

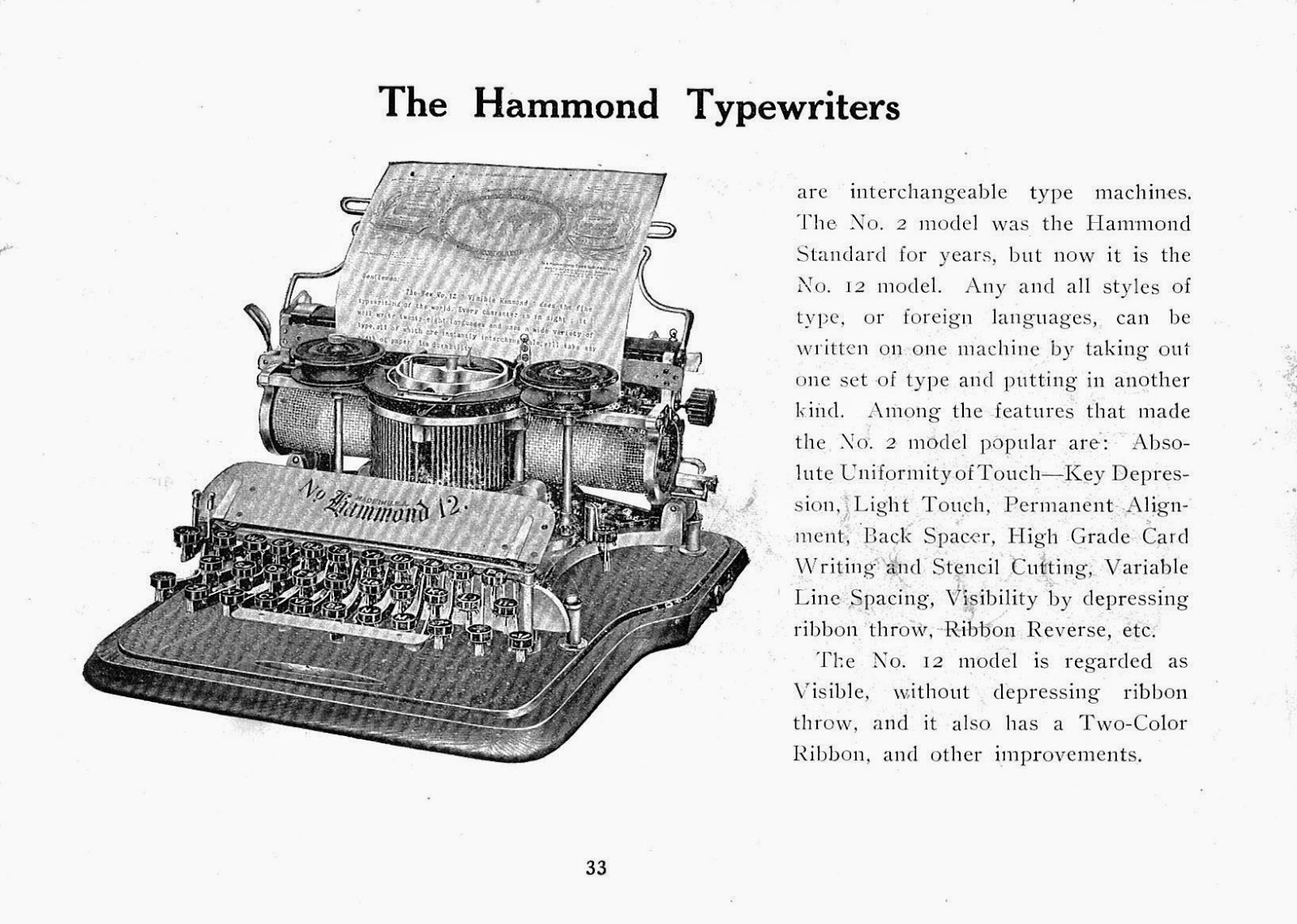

In the interim, Burlingame had had more than a little help from his West Coast "friends". Those "friends" had used illegal means to incorporate Burlingame's work with that of a Californian inventor, Adolph Schaar. Schaar's invention used a Hammond typewriter keyboard and received messages by tape, Burlingame's used a Stearns Visible typewriter and received messages in page form. But the Burlingame only worked from room to room, not over truly long distances, like the Murray. The modus operandi of the Burlingame company's directors, led by "Blind Boss" Chris Buckley and his cohorts, was to take one man's invention and profit from it unlawfully, when they weren't entitled to any share of the proceeds. Even putting royalties to one side, Schaar got almost none of the subsequent credit for the telegraphing typewriter, Burlingame was given far too much of it.

In the end, it didn't really matter. Neither the Schaar nor the Burlingame machines ever went into full production. It's the fraudulent behaviour of the Burlingame company that counts.

J.J.Montgomery discovered the electric rectifier while working on the Schaar-Burlingame telegraphing typewriter.

After Buckley and crew employed aviation pioneer John Joseph Montgomery (1858-1911, "The Father of Basic Flying") to get the Schaar-Burlingame machine working, and in the process Montgomery inadvertently stumbled upon the electric rectifier, the Burlingame mob tried to cash in on Montgomery's discovery, at half the going price ($500,000). (A rectifier converts alternating current [AC], which periodically reverses direction, to direct current [DC], which flows in only one direction.) How innocent was Burlingame in all of this? Well, maybe some of the sins of San Francisco stuck. Five years after the telegraphing typewriter jig was up, on January 7, 1914, Burlingame was sent to jail for two-and-a-half years and fined $10,100 for another fraudulent business activity, across the other side of the country in New York. He had helped swindle investors in the Radio Telephone Company out of millions of dollars. Now that was an act of the devil!

The Burlingame telegraphing typewriter was launched on the market in California in April 1908. The subsequent advertising campaign for it in the Eastern States, starting in October 1908, was extraordinary. The cost of almost daily full-page adverts, mostly containing endorsements for the machine from around the country, must have cost a large fortune - let alone the wide supply of Stearns typewriter-fitted machines, assembled by the US Wireless Printing Telegraph Company in San Francisco, to be endorsed in the first place.

Not all that many of these virtually worthless $10 shares were actually sold from May 1908 to January 1910.

These enormous initial outlays weighed down Burlingame's "invention" before it had even had a chance to get off the ground in the marketplace. Some sales might have helped justify the vast amounts involved in what was listed as a $15 million concern. Indeed, 120,000 of 150,000 $10 shares had been "sold", so at least on paper the Burlingame fraud reached $12 million. As it turned out, no Burlingame machines were ever sold.

The subterfuge included establishing a stock-selling company called Burlingame Underwriters, which allegedly owned 62,000 of the shares. But in real hard cash terms these realised just $82,323 - in other words, less than $1.33 for each $10 share. By the end of 1910, Burlingame shares were worth a mere 20 cents!

Long before then, events had exposed the awful truth, that the Burlingame enterprise was a fake, and thus worthless. The Burlingame company's "stock-jobbing" had become a US-wide scandal. ("Stock-jobbing" is the speculative short-term buying and selling of securities with the intent of generating quick profits. The term is largely used in reference to the South Sea Bubble - an 18th-century stock that literally wiped out the savings of many British citizens.)

The venture was founded on the illegal transfer of the rights to a real "teletyper", the Schaar Tel-Autoprint, itself doomed by these business manipulations to be another Californian flop.

Burlingame had acquired the backing of an Indiana real estate "capitalist"John W.Flinn (1865-), but pretty quickly the illegal means by which the enterprise was being put together and funded, and the machines assembled, started to unravel. It turned out the Burlingame Telegraphing Typewriter wasn't by any means Burlingame's original invention, but was based on a Tel-Autoprint invented by Los Angeles telegraph reporter Adolph H. F. Schaar (1870-1940), of Oakland, California, in 1906. Schaar sold the rights to the USWPTC in 1907, and that's when the misdeeds related to his invention began.

Schaar's "Tel-Autoprint"

The first sign of "trouble at mill" came in mid-February 1909, when USWPTC stockholder Edmund Burke sued San Francisco's infamous "Blind Boss", Christopher Augustine Buckley (1845 -1922), Flinn, Burlingame and other directors for $500,000, claiming Buckley had fraudulently sold all the assets of this company to Flinn and Burlingame's venture without proper authorisation. (Vilified as "what men call a crook", Buckley was routinely accused in newspapers of corruption, bribery and even felonious crime.)

Buckley tried another similar stunt when he got Professor Montgomery of Santa Clara College to work on the Schaar machine. Montgomery discovered an electric rectifier in the process and Buckley and his Schaar project cohorts claimed partnership in an invention valued at $500,000. In 1911 the courts found in Montgomery's favour.

"Blind Boss" Buckley was not blind to the possibilities of a rort.

The USWPTC assets which Buckley had manipulated away from the Tel-Autoprint investors included the rights to Schaar's invention and the company's factory site in Los Angeles, secured to make the Tel-Autoprint in June 1907 (when advertising for the machine started to appear in the San Francisco Call).

As early as August 1907, one of the team of directors who had joined Flinn and Burlingame in the Buckley scam, one W.H.Valentine, had claimed in Reno, Nevada, that the machine was his invention. This ruse was quickly exposed by the Arizona Republican in Phoenix, which correctly credited Schaar. As well, the Republican corrected the impression that multi-millionaire Californian Clarence Hungerford Mackay (1874-1938) hadn't already approved the Schaar machine for use by the Postal Telegraph & Cable Corporation, which had just laid a cable between New York and Cuba. Mackay, who took over as Postal president upon the death of his father in 1902, also supervised the completion of the first trans-Pacific cable between the US and the Far East in 1904.

Postal boss Clarence Mackay backed the Schaar invention.

One way or another, strenuous efforts were made by the Burlingame enterprise directors to deny the fact that Schaar had invented the device, including an April 1908 Los Angeles Herald article which gave credit for the Tel-Autoprint to Burlingame:

"His" Tel-Autoprint? Los Angeles Herald, April 3, 1908, before the jig was up.

The first advertisement for the Burlingame machine appeared in the Los Angeles Herald in April 1908 and acknowledged Schaar's invention. Subsequent advertising, in both California and the Eastern States, did not.

The Tel-Autoprint was also variously referred to in late 1907 as the "Teletype" and the "Telewriter", the former using a Hammond typewriter (as did the Schaar).

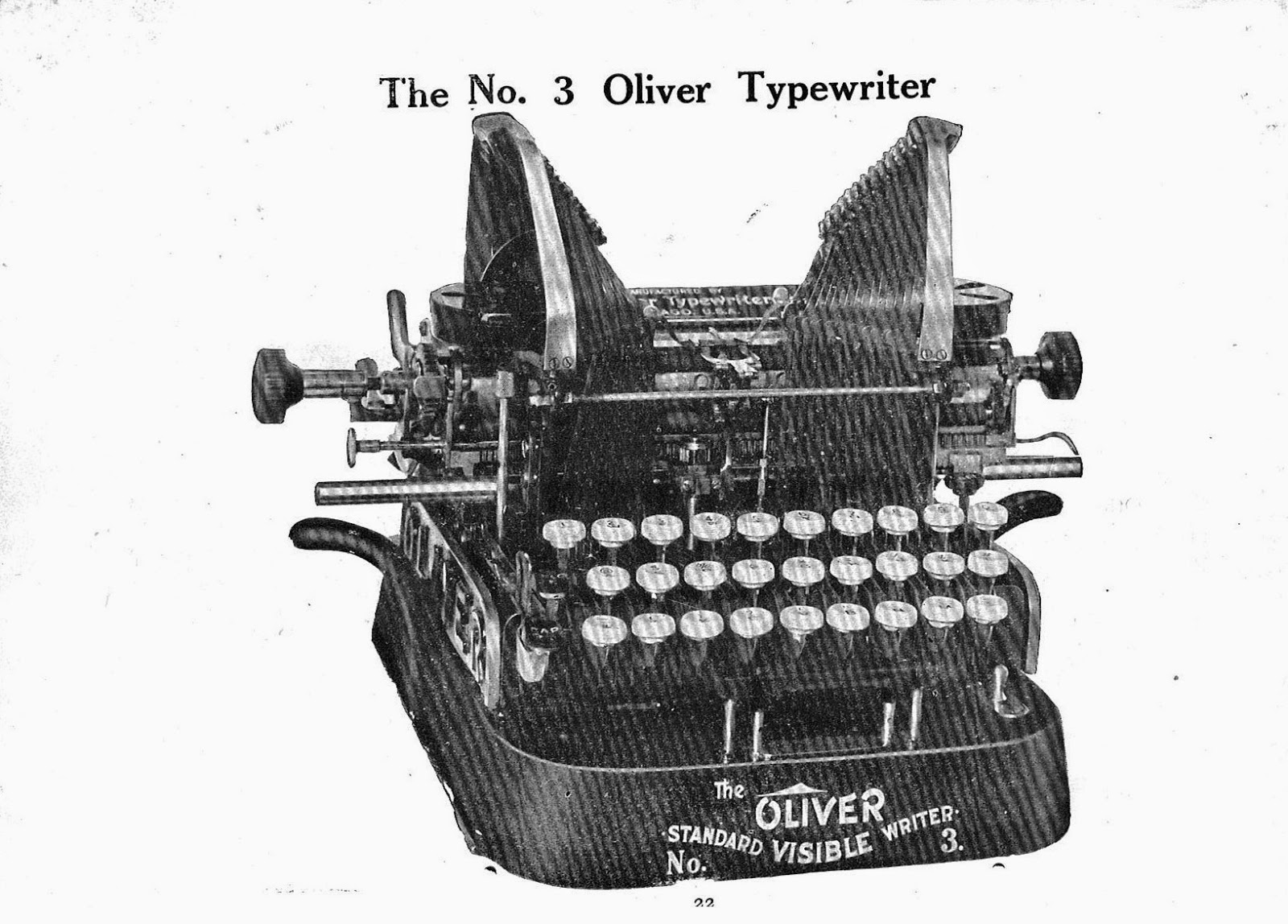

However, it is easy to confuse this work with that started in the same period by the Krums of Chicago. Charles Lyon Krum (1852-1937) and his son Howard Lewis Krum (1883-1961) took up the work of Frank Dillaye Pearne (1876-1927) and developed a teleprinter with Joy Morton (1855-1934) and his son Sterling Morton (1885-1961). Krum machines used Oliver and Blickensderfer typewriters, but were also influenced by the Hammond keyboard.

The first Eastern States advertising for Burlingame's machine appeared in October 1908:

After Edmund Burke had taken Chris Buckley to court in California and exposed the Burlingame sham for what it was, in February 1909, Burlingame himself hightailed it to New York, looking for other ways to amuse himself with his ill-gotten gains, such as investing in an aircraft.

Burlingamemay have been the first American to fly a monoplane.

But he also got involved in another fraudulent business deal, and this time the law soon caught up with Burlingame. In early 1914 he was jailed for two-and-a-half years, as well as being fine $10,100.

There are plenty of Elmer Burlingame profiles online, many asking what became of him and his company post-1910. Not one of them mentions he was locked up from 1914-16.

By 1912, after the Consolidated Printing Telegraph Company of New York had taken over the stock of the Burlingame company and listed itself as also being worth $15 million - but had promptly gone bankrupt in June 1911 - Munsey's Magazine was calling the Burlingame enterprise "notorious". (Consolidated, by the way, announced it had also acquired the patents, among others, of the perforated typewriter paper device that Gustaf Swenson, of Pittsburgh, had originally assigned to Underwood, the printing telegraph system of New Jersey's Frank B.Rae, assigned to the "New Burlingame Telegraphing Typewriter Company", and the printing telegraph, telegraph transmitter and printing machine of John C. Barclay of New Jersey.) Only at this late stage were there promises of "perfecting a machine"! Sure enough, a machine was produced and it did work. But it didn't save Consolidated from its inevitable fate. The enduring bad vibes from the Burlingame enterprise quickly killed it off. Investors, nonetheless, were still keen to get their hands on the wide range of patents relating to a telegraphing typewriter and an American Printing Telegraph Security Company was formed, with more modest capital of $100,000 ($10 a share). Consolidated shareholders got no purchase in the later company.

In outlining the sordid history of Burlingame's "once famous fake", Munsey's said each dollar invested in it and Consolidated ("hopelessly bankrupt ... dead and gone") was a "total loss".

Dreaming of a dark future? A young Elmer Burlingame in Aderdeen, Dakota Territory, with his father Freeborn Wanton Burlingame and mother Isabelle Ann Larkin Burlingame.

So who was the man behind the Burlingame fiasco? Was he simply an inventive, ambitious young man who innocently got caught up with a bunch of criminals? Or was he a knowing party to all this?

Elmer Allah Burlingame was born in Green Lake, Wisconsin, on June 13, 1879. The family moved to LaPorte, Indiana, in 1895, where Elmer graduated from LaPorte High School and in 1899 started work for the LaPorte Telephone Company.

After the collapse of his fake telegraphing typewriter project, in 1910 he moved to Norfolk, Massachusetts. After being released from jail, in 1917 Burlingame was working as a machinist for tin platers Wimslow Brothers in Chicago. He later moved to Gary, Indiana, to rejoin his parents, and in 1930 he was back in business on his own, running an electrical shop. This didn't survive long, either, and Burlingame followed his parents to Long Beach, California, where he died in San Pedro on January 23, 1939, aged 59.

An obituary stated Burlingame“lost his patents to [his] invention to a large company which ultimately developed the device and made a large fortune from it, although he himself never received the reward entitled to him.” This is patently untrue. Any real rewards were actually due to Schaar. And he got none, as there were none to distribute.

As for Burlingame being, as one biographer had it, "a combination of Tesla, Edison, Steinmetz, Einstein, Alger and Bell", I don't think so. The biographer himself added, "It was pretty putrid stuff."

%2B-%2BCopy.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)