The Rochester was to be a thrust-action typewriter. Presumably the American Pocket Typewriter was one, too?

It's almost three years now since I posted on Wellington Parker Kidder's ultimate typewriter, the tiny Rochester, considering it then as now to be the portable of my wildest dreams. At that time, in late July 2011, it was my belief that the Rochester was never made, and that Kidder had died in Manhattan on October 2, 1924, with his ambition of seeing this "pocket rocket" go into production unfulfilled.

Kidder's Rochester was clearly to be a very basic typewriter, with a one-piece, folding frame - perhaps even more basic than the American Pocket Typewriter. Kidder applied for the patent for the Rochester in November 1922, five months after the American Pocket Typewriter had appeared, and the patent wasn't issued until nine months after his death. But wait ... there was an earlier design!

It turns out, however, that an earlier version of the Rochester was made, at the very least as a prototype. It was called the American Pocket Typewriter, and an example of it is in the Dietz Collection at the Milwaukee Public Museum. The mystery surrounding these two models is compounded by the fact that the American Pocket Typewriter was produced in June 1922 and the Rochester was vaunted for production exactly one year later.

Master typewriter designer Wellington Packer Kidder (1853-1924)

Trying to work out the truth behind these machines is not helped by false leads from the Milwaukee Public Library and what publications do mention the American Pocket Typewriter and the Rochester. These do offer a few hints, but one needs to dig deep to get to the actual facts behind them.

For example, a catalogue of the Dietz Collection written by George Herrl in 1965 refers to its American Pocket Typewriter as being produced in 1926 and "devised" by "A.L. Legett of New York City". Herrl says the model was donated to the Dietz Collection by a "Mr N.P. Zech of Chicago", "one of the principal backers of the enterprise". Neither statement is entirely accurate.

In part, it was the other way around - with Leggett initially getting the rights from Rochester Industries. Yet the late Paul Lippman, in his American Typewriters (1992) got much closer to the mark. In Lippman's defence, he took his spelling of "Leggatt" instead of "Leggett" from Typewriter Topics' 1923 A Condensed History of the Writing Machine, and from issues of Typewriter Topics in March and June of 1922. That Lippman lumbered the Rochester, Leggett and American Pocket typewriters all into the one entry means that he had rightly figured they were all essentially the same machine.

The "Legett" did not have the initials "A.L." but was Alfred John Leggett, a Rochester (not New York City) banker. He was born in Rochester on June 11, 1880, and was for many years assistant secretary (his position when the APT was made) and later assistant vice-president of the Rochester Trust and Safe Deposit Company. He started work with the company as a teenager, as a bank clerk and receiving teller. Leggett retired to Pinellas, Florida, and died there on March 6, 1938, aged 57.

![]()

![]()

The "Mr Zech of Chicago" was in fact Nicolaus Paul Zech, who at the time of backing the APT enterprise was in East Orange, New Jersey, working as an auditor for a brokerage company. He was born in Chilton, Wisconsin, on July 18, 1879. The family moved to Milwaukee, where "Nickie" started work as a bookkeeper, having graduated from Canisius College, New York. As an accountant, he went on to become vice-president and comptroller of the doomed investment bank the Middle West Service Company, while based in Wilmette, north of Chicago. He died there on November 8, 1947, aged 68. Zech and his German-born father, Johann Nepomuk Zech (1846-?), are most famous for inventing, in Milwaukee in 1899, a vehicle brake system which was adopted by New York car companies. Nicolaus advanced this in 1909.

Typewriter Topics, March 1922

OK, so Leggett being a Rochester banker and businessman, it makes sense that the production of the earlier version of the Rochester typewriter should be proposed by someone from that city. As well, it makes sense that the American Pocket Typewriter was to be manufactured in Boston, near where Kidder lived. But hang on - why would Rochester Industries, of which Kidder was consulting engineer, have to acquire the Leggett Portable Typewriter Company in order to make the Rochester? Surely it was Kidder's machine? And in developing the Rochester, Kidder had himself described it as a “pocket typewriter”, one which could fit in “an ordinary overcoat pocket”.

So yes, the pocket typewriter was Kidder's idea. Perhaps the sequence of events might explain how all this came to pass.

Typewriter Topics' 1923 A Condensed History of the Writing Machine

To begin with, the American Pocket Typewriter that Leggett attempted to get manufactured in Boston was certainly designed by Kidder, yet the patents rights to it had been assigned by Kidder to - none other than Harry Bates! That's right, the same Harry Bates who was an "acquirer" of other people's typewriter designs in the class of Harry A. Smith. Now the name of Bates has not appeared in any published print works which mention the American Pocket Typewriteror the Rochester.

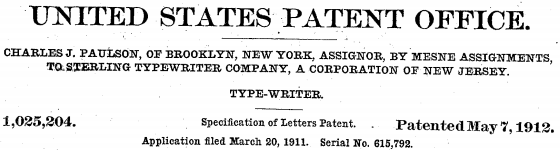

But in 1920 Bates went on to claim this design as his own, calling it a "midget typewriter". Here, very clearly, is the design of the American Pocket Typewriter, with the words "Harry Bates Inventor" quite evident:

In January 1923, 10 months after the Leggett bid was launched, Office Appliances: The News and Technical Journal of Office Equipment announced, under the headline, “To Produce Midget Typewriter”: “Old Typewriter Man [Kidder] Invents Unique Machine and Interests Group of Well-Known Business Men [Bateset al] in Its Manufacture”.

The item said reports of this “midget typewriter” had first appeared in New York daily newspapers in late December 1922, with the announcement of the organisation of Rochester Industries. The plot decidedly thickens!

Technically, this story was correct to identify Bates as the "inventor", but pointed out that Bates had “developed it in association with Wellington P.Kidder, consulting engineer of the new company [Rochester Industries]. Both gentleman have invented a number of mechanisms in the typewriter field.”

Kidder's work on the Pocket-Rochester actually started in 1918 and in July 1919 he assigned the design to Rochester Industries (so it was around three years before the Leggett bid). Interestingly, while all this business with Leggett and Bates was going on, Kidder applied to renew the patent on Christmas Eve 1923. It was issued in July 1924, just nine weeks before he died - and too late for him to change the course of events.

Kidder had applied for an earlier patent on this machine in November 1918. When it was issued, in July 1921, he had assigned one third of it to Bates and two-thirds to the International Lettergraph Corporation of 76 East 56th Street, New York (incorporated as a “foreign business corporation” in Delaware on February 17, 1920).

Meanwhile, in September 1920, Bates went ahead and applied for a patent for the machine in his own name, assigning it to Rochester Industries and calling it an “Incased Collapsible Typewriter” (of “an otherwise compactible nature”). This was issued in late December 1924, almost three months after Kidder had died.

The collapsible "pocket" typewriter assigned wholly to Bates

An interesting aside here - as if there aren't enough already - is that the slip of paper inserted on the Rochester platen in the image at the top of this post is addressed to the Hulse Manufacturing Company of Geneva, New York. This plant was a subsidiary of the Corona Typewriter Company, one to which Corona moved machinery from Brooklyn in 1920. It bought the Lewis Street factory from National Wire Wheel Works. SCM shut down the plant in April 1975 and the building closed in 1992. Did Kidder plan to have the Rochester built there, or was he just checking on the "collapsible typewriter" patents?

Corona's Hulse plant in Geneva, NY

Confusing? Obviously the US Patents Office in Washington DC found it all pretty confusing, too!

The Rochester Silent, with "type-head-actuating" mechanism

Harry Bates was born in Greenbush, New York, in 1868, the son of an engineer. He began work as a clerk, become a stenographer in 1889, a reporter with the Albany Journal in 1891 and Albany correspondent for the New York Herald in 1896, He was editor of the Albany Star-Eagle in 1899-90 and Albany manager for Smith Premier in 1907. He then became a long-serving and inventive advertising manager for Underwood, for whom he had invented the typewriter pay station, an educational typewriter and a typewriter table.

Once the multitude of patents on the Pocket-Rochester had all expired, in the mid-1930s Bates moved in again. The “midget typewriter” idea suddenly re-emerged with a large number of patents assigned to the Bates Laboratory of New York. These new designs came from Bates and, in some cases, Bates and a Joseph Lee Sweeney. They included noiseless (developed by Raphael Atti from Kidder’s original concepts), compact and toy versions. These patents were issued right up until 1941.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)