This is a story about capital punishment,

the possibilities of rehabilitation,

of mercy, clemency and of forgiveness

Paul Crump served 39 years in Cook County Jail but was spared from the electric chair when he gained international notoriety and parole after writing the novel Burn, Killer, Burn! on a Remington SJ manual standard typewriter. It added 40 years to his life. The typewriter was acquired through a prison newspaper campaign launched by Crump's friend and then fellow prisoner, the Spanish Civil War veteran and legendary Chicago painter, poet and one-armed pianist Edward Ross Balchowsky (below, 1916-89). Ed helped Crump with his early writings. Every man has got something to give,

And if a man can change,

then a man should live.

- Lines from Paul Crump by Phil Ochs

(see full lyrics below)

Crump, below, had 15 dates with the electric chair in Cook County Jail.

Five years ago I had no hesitation in agreeing to help a Sydney couple whose son had been locked up for life in a Thai jail on charges of drug trafficking. The young man wanted a portable typewriter so he could start a Technical and Further Education (TAFE) course. Enormous difficulties in convincing the Thai authorities to allow the Olivetti Lettera 32 into the jail were eventually overcome. Even then jailers tried to put the Olivetti out of commission. The Lettera 32 withstood this harsh treatment, and one was left hoping the typewriter might provide a valuable step forward on the road to rehabilitation, and perhaps one day to a life beyond those jail walls. Myuran Sukumaran and Andrew Chan may not be so lucky.

Sukumaran has made a personal plea for mercy to Indonesian President Joko Widodo, painting a portrait of Widodo and signing it with the words "People can change". I wonder if he knows the story of Paul Crump? Or of the song by Phil Ochs? Sukumaran led an art studio for his fellow prisoners during his time in Kerobokan prison on Bali and was awarded an associate degree in fine arts by Curtin University in Western Australia. At Kerobokan he also taught English, computer, graphic design and philosophy classes to fellow prisoners. The prison governor described Sukumaran and Chan as model prisoners and testified in court that they should not be executed because of the positive influence they had in jail. Chan also organised courses, led the English-language church service and was a mentor to many. He claimed God said to him, "Andrew, I have set you free from the inside out, I have given you life!"Andrew Chan, left, and Myuran Sukumaran

Our American friends would almost certainly be unaware of this, but the story which has dominated Australian television and online news in the past few months concerns the impending execution in Indonesia of two Australian men caught attempting to smuggle heroin into Australia from the Indonesian island of Bali in April 2005. In Indonesia, crimes against laws relating to the production, transit, importation and possession of psychotropic drugs and narcotics are punishable by death. Andrew Chan, 31, and Myuran Sukumaran, 33, were the alleged ringleaders of the so-called "Bali Nine", a group of young Australians who were arrested at Ngurah Rai International Airport and the Melasti Hotel in Kuta and charged with planning to smuggle 18lb of heroin out of Indonesia.Chan and Sukumaran are at the Nusakambangan Island prison, along with five other foreigners condemned to execution by firing squad. The others are Rodrigo Gularte, a Brazilian who suffers from paranoid schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with psychotic features, Frenchman Serge Atlaoui, Nigerians Raheem Agbaje Salami and Silvester Obiekwe Nwolise and Filipina Mary Jane Fiesta Veloso. In January, Indonesia executed a Dutchman, Ang Kiem Soei, another Brazilian, Marco Archer Cardoso Moreira, a Nigerian, Daniel Enemuo, a Malawian, Namaona Denis, an Indonesian woman, Rani Andriani, and a Vietnamese woman, Tran Bich Hanh.In the main, news coverage in Australia does not tend to reflect it, but it would seem the country is evenly divided on the impending executions of Chan and Sukumaran. A special snap SMS Roy Morgan Poll in late January, commissioned by the current affairs program of a national radio broadcaster, showed a slender majority (52 per cent) believed Australians convicted of drug trafficking in another country and sentenced to death should be executed. A much larger majority (62 per cent) said the Australian Government should not do more to stop the executions. It might fairly be supposed the poll reflected the regard many Australians hold for Indonesia's sovereign right to enact its own laws and carry out sentencing passed down by its open courts. Indonesia is, after all, a republic which is, in some important ways, more advanced than Australia: it has its own democratically elected head of state, with no symbol of a former ruler on its flag.In another sense, the Morgan poll also reflected the fact that those compassionate Australians vehemently opposing the executions of Chan and Sukumaran have not been aided in their efforts to achieve clemency by a clumsy, bumbling Australian Government, one which seems to be constantly stumbling from one political faux pas to the next. (After knighting the Duke of Edinburgh, the latest embarrassment from our Prime Minister is his call on the funding of "lifestyle choices" of Aboriginals living in outback areas). Heavy-handed threats to Indonesia, especially in regard to aid, have been met by counter-blustering, such as a vow that Australia faces a "tsunami of asylum seekers" on incoming refugee boats. None of which does Chan and Sukumaran any good whatsoever. The truly sad part is that, if Chan and Sukumaran are granted clemency, this Government will claim the credit, when it will have only come about through Indonesian benevolence, not from any Australian pressure. With its bravado, the Australian Government is trying to win back public favour (another Morgan poll showed Tony Abbott is the preferred governing party leader by a mere 14 per cent) - which is another thing entirely from actually trying to save the lives of Chan and Sukumaran.The hope of Indonesian mercy brings me to another case in which a man sat on Death Row - and was saved, one could say, by a typewriter, a Remington SJ manual standard.When Paul Orville Crump died of pneumonia and lung cancer at the Chester Mental Health Center in Chicago on October 11, 2002, he had served 39 of his 72 years in prison for killing a security guard in the armed robbery of a Chicago meatpacking plant in March 1953. But he had had 40 years added to his life, largely through his novel Burn, Killer, Burn!

Crump, born in Chicago on April 2, 1930, was in June 1953 sentenced to die in the electric chair. He had 15 execution dates before the sentence was changed to 119 years by Governor Otto Kerner on August 1, 1962, just 35 hours before Crump was scheduled to be killed. He was paroled in 1993 but struggled to adapt to freedom, and with the alcohol and mental illness issues that would compel his sister Gwendolyn Jones to get an order of protection against him.

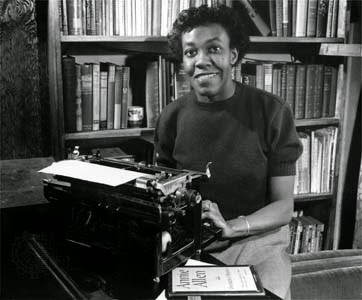

While serving his long sentence, Crump, inspired by a visit from the writer Nelson Algren, above, began reading classic literature and wrote his novel, about a murderer who commits suicide rather than be executed. It was published in 1962. Those who backed Crump's efforts for parole, including authors James Baldwin and Gwendolyn Brooks (below), the Reverend Billy Graham and the gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, viewed the book as proof that he had been rehabilitated. Crump was also the subject of a documentary [The People versus Paul Crump] by William Friedkin.In 1960 Friedkin had been invited to a party by cultural maven Lois Solomon (later Lois Weisberg, Chicago cultural affairs commissioner), who had heard about Crump from Balchowsky's friend, the writer Felix Jacques Singer (1928-). Singer, author of 1959's These Seventeen: Sixteen Stories and One Essay, was a social campaigner who took the Freedom Ride from Montgomery to Jackson in 1961.Friedkin, back then a man strongly opposed to the death penalty, was introduced to Father Robert Serfling, the Death Row chaplain at the Cook County Jail. "I asked him had he ever met anyone on Death Row whom he thought was innocent," Friedkin said. "He told me about Paul Crump." In the seven years of awaiting his execution, Crump had become a model prisoner and, in the opinion of the warden, Jack Johnson, fully rehabilitated. "Johnson had executed at least two people by then and he didn’t want to execute Crump," Friedkin said. (See an interview with Friedkin here).Friedkin, right, on the set of The French Connection

Four years ago, writing about "The forgotten case of Paul Crump"in the Chicago Tribune, David Weiner raised fresh doubts about Crump's guilt.

![]()

"Before William Friedkin became famous for directing The French Connection and The Exorcist, he was a television director for WTTW in Chicago. In 1962, Friedkin made a movie about Paul Crump, a Cook County Jail inmate scheduled to be executed in the jail's electric chair."

Weiner didn't mention the fine details, which are that Crump had confessed and was convicted of killing father-of-five Theodore P. Zukowski, 43, the chief guard who tried to stop an attempted $20,500 robbery at the Libby, McNeil & Libby Food Products offices at the Chicago Union stockyards on March 20, 1953. Crump said he shot Zukowski with a .38 calibre revolver he took from another guard. Crump was one of four of the five suspects arrested on March 25 (the fifth, Hudson Tillman, 19, had turned state's evidence, leading to the other arrests). The actual proceeds of the robbery, $2900, was quickly recovered. On June 19, Crump, by then 23, was sentenced by a Criminal Court jury to death in the electric chair, the execution date being set for November 14 by presiding case judge Frank R. Leonard in August, when Tillman was given 15 years. David Taylor, 24, his brother Eugene, 22, and Harold Riggins, 22, were each sentenced to 199 years jail. An alleged escape attempt by Crump was foiled in late October.

Weiner went on: "During his trial, Crump claimed he was tortured into confessing he had committed the crime [that is, the killing of Zukowski]. After his conviction and being sent to the jail, Crump became a "model prisoner" - even writing a book, Burn, Killer, Burn! - and many people called for Crump's sentence to be commuted.

![]()

"Friedkin was hired to make a documentary about Crump that was to air on what was then known as WBKB, Channel 7 TV, the night before Crump's execution. Because of the controversy surrounding Crump, his allegations of torture and his subsequent rehabilitation, Jim Wagner, Friedkin's lighting director, alleged that the movie was screened for then-Mayor Richard J. Daley and the State Street Council, whose members were major sponsors of WBKB's programming. Even though the film was narrated by Joel Daly, the station's then-leading news anchor, and was considered accurate and factual, the scenes depicting Crump's alleged torture caused such an uproar WBKB was forced to pull the film. As producer of the film, WBKB had allegedly confiscated all copies of it. But Friedkin hopped on a plane to Springfield and showed a 'bootleg' copy to then-Governor Otto Kerner*. Less than an hour after viewing the film, Kerner commuted Crump's sentence to 199 years in prison.

![]()

"The film was never aired* and it was assumed all copies were destroyed. No one wanted to bring to light the allegations of police torture and the damage it would cause to the city. Remember - this was before the Civil Rights movement came to a highly segregated Chicago - and Chicago's African American community was years away from having a meaningful say in the running of the city. The racism implicit in Crump's 1953 torture - even if true - would cast an onerous cloud over the city's image.

"Now, some 50 years later, a cop - former Chicago Police Lieutenant Jon Burge - is on trial for lying about torturing prisoners and the dark side of our city is finally being brought to light for all to see. Democrat Michael Dukakis lost the 1988 presidential election over a fumbling answer on capital punishment. He tried to 'intellectualize' his way around the question instead of showing true emotion. Just like the way Americans judged Dukakis, we also have to judge Jon Burge."

*The People versus Paul Crump was screened and was the Golden Gate Award Winner for Film as Communication at the 1962 San Francisco International Film Festival. A digitally restored version of the film was released by Facets in May last year. Also, it was Red Quinlan, general manager at WBKB, who sent the film to Kerner, who watched it and sent Friedkin a letter. "Which I still have," Friedkin said. "He said, 'I was extremely moved by your film … I’ve decided to parole [Crump] to a life in prison without the possibility of parole.'" The track Paul Crump appears on Phil Ochs' albums The Early Years and A Toast to Those Who Are Gone

In the state of Illinois 'bout nine years ago

A cold blooded killer, he went against the law

He killed a factory guard when his robbery did fail

And they caught him and they threw him into jail

He lay there in his cell, locked up with his hate

Not many men knew of him and less cared for his fate

And he knew no peace of mind when his trial was comin' by

The judge said, "You are guilty you must die"

But Paul Crump is alive today

He's a sittin' in a cell, he's got somethin' to say

Every man has got something to give

And if a man can change, then a man should live

They sent him to Cook County Jail, a jail known far and wide

Where pity was a stranger and brave men often cry

They locked him in the death row to count the days before

To the day they came a knockin' at his door

But another warden came along, Jack Johnson was his name

He knew how prison living could drive a man to shame

He had no need of pistols in a solitary cell

When a word of trust would help him just as well

Now Paul Crump is alive today

He's a sittin' in a cell, he's got somethin' to say

Every man has got something to give

And if a man can change, then a man should live

Between the warden and the convict, a friendship slowly grew

And one learned from the other that a man can live anew

Then the warden called the convict, "You must leave the devil's plan

The time has come for you to be a man"

Then the convict found religion and he started him to learn

He wrote himself a novel called 'Burn, Killer, Burn'

And as his dying day grew near, to the warden he did cry

"You must pull the switch and I must die"

But Paul Crump is alive today

He's a sittin' in a cell, he's got somethin' to say

Every man has got something to give

And if a man can change, then a man should live

It was up to Governor Kerner to keep him from the grave

Was rehabilitation a reason to be saved?

The hour was comin' closer, the word was spread around

A new and better answer must be found

Well, the electric chair was cheated, the convict didn't pay

A new concept of justice was born and raised that day

Now throughout this peaceful land there are others set to die

What better time than now to question why?

But Paul Crump is alive today

He's a sittin' in a cell, he's got somethin' to say

Every man has got something to give

And if a man can change, then a man should live

![]()

![]()

%2C_1833-1880_2.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)