↧

Getting there: Continental portable typewriter - a work in progress

↧

Christmas Typewriters #8

↧

↧

The Beautiful and The Damned: Gold-Panelled Corona 4 Portable Typewriter

The Norma Desmond of Typewriters,

once glittering, now fading

"You used to be big."

"I am big. It's the drawband that got small."

"They took the idols and smashed them, the Underwoods, the Royals, the Valentines!

And who've we got now? Some nobodies!"

And who've we got now? Some nobodies!"

"There once was a time in this business when I had the eyes of the whole world!"

"No-one ever leaves a star. That's what makes one a star."

"The stars are ageless, aren't they?"

"We don't need two typewriters, we have a typewriter.

Not one of those cheap new things made of plastic and spit, a Corona 4."

Not one of those cheap new things made of plastic and spit, a Corona 4."

This gold-panelled Corona 4 portable typewriter, serial number V1A08642 (1929), is a flawed beauty which has had one foot in the grave for the entire decade I have owned it. Many times in those 10 years have I taken it out to remind myself of why I can't use it, and each time I have literally stumbled upon the complexity of the drawband arrangement. In the past, it has even crossed my mind to use it as a spare parts machine. But I just couldn't bring myself to do that.

The other day I was looking at my red Corona 4, the blue one with gold panelling, and this one, trying to decide which of the three I will definitely keep (it's the red one, I know). Yet again, as I weighed up the black model, I looked at the mainspring and thought, "I should be able to fix this. Why haven't I fixed it already?" It's called selective memory. Deep down, I knew the answer. I was just being blind to defeat, refusing to accept the awful truth. Behind my thoughts was a long-standing and overwhelming reluctance to pass on this machine. But yet again, after two days of effort, I have given up on it.

For all that, I was determined to feel and see it typing, if only just the once. So I jury rigged an arrangement with the drawband across the back, attaching it to the margin setter, which I pushed to the far right, just so I could at least type some short lines. Getting a few words out of it only made me feel all the more sad and frustrated, that I had failed for the umpteenth time to turn this beauty back into a fully functioning machine. Damn! And damn again ... I do love you, Norma Desmond, I just can't live with you anymore.

↧

Christmas Typewriters #9

↧

Feeding Paper into a Marx Dial Toy Typewriter

Ottawa toy historian and award-winning author (of Light Bulb Baking) Todd Coopee wrote asking about a Marx Dial toy typewriter he has bought. "It appealed to me because it is tin-litho and from Louis Marx & Company," said Todd. "However, for the life of me, I can't figure out how one would load paper into it. I don't want to use it or anything, but I just want to know how to do it! A bit of a puzzle that I can't figure out. I'm hoping you might have some time to provide me with a few quick tips."

So I put together this video with the requested tips, in case anyone else has the same question:

↧

↧

Return of 'The Life of a Typewriter Technician'

How I Stole Back

the 'Stolen' Typewriter

By Michael Klein

Episode 4

Previously I related how I came into typewriters, as a young wet-behind-the-ears school leaver being offered a job with a local office equipment supplier.

Let me continue on with the story …

The small typewriter repair organisation I worked with had the whole gamut of customers, ranging from some very big service contracts with companies that had hundreds of typewriters down to solicitors and estate agents that only had one or two machines. We also did visits to private homes to repair typewriters, but this was rarer, as the home user didn’t want to pay a reasonable rate to make it worthwhile for us. The bigger service contracts were much more lucrative.

We also had some very dodgy customers and one in particular comes to mind.

Picture a young, naive young lad, just new to the job of typewriter technician, very enthusiastic and always looking for ways to please the boss.

One evening I was watching a television current affairs program (remember those programs after the nightly news, that made an art form of having reporters chasing crooks down the street, trying to question them about some dodgy scam or some such?). I happened to notice one of these reporters entering an office that looked vaguely familiar, and as he started his interview, I recognised the person who was trying to shield his face from the camera as he was making a bolt to get away from the reporter … it was one of our customers!

I remember this particular customer, as he was late in paying us for a new typewriter that we had delivered to him. I had been sent on missions to his office several times to deliver overdue accounts for the machine (an Olympia SGE45, as I recall - this was a very popular electric that we sold successfully into schools and offices. It was robust yet compact, which means it didn’t take much desk space. But I digress).

Well, appearing on a current affairs show is usually the death-knell for a company - it either goes bankrupt or goes underground, to surface again with another scam operation. Seeing this chap on TV made me feel I had to act quickly, and what better way to impress the boss than to get payment for said typewriter before this shonky company sold off its (unpaid for) machine in a fire sale due to bankruptcy?

The plan was hatched. I would arrive at this office first thing in the morning and demand that the dodgy typewriter 'owner' pay his bill before his company went under.

The next morning, I arrived at the office, trembling with both fear and excitement. I knocked on the door, entered the reception area, and waited. I could hear voices in the back tearoom, laughing no doubt about having snubbed noses at the reporter in the previous night’s TV program. I waited for a minute or so, and made a few discrete coughs to try and draw attention to this most unlikely debt collection officer loitering in the office. But whoever was in the tearoom was so engrossed in conversation that they didn’t hear me through the partitions.

On the spur of the moment, having spied the typewriter on the secretary’s desk, I sauntered over to it and pulled out the cord from the machine. (Typewriters in those days were transitioning to having an international DIN-type cord that plugged into the back of the machine, rather than the cord being hard-wired, which was lucky as it meant I didn’t have to rummage under the desk to unplug it; it was simply a matter of leaving the cord behind).

Well, with the typewriter under my arm, I hot-footed it outa there! Like a scene from a cop movie, I decided to take the fire exit rather than the lift. I must have thought I was heisting a million dollars rather than an $800 typewriter.

My heart was racing as I made my way to my employer’s typewriter shop to proudly inform him of my deed, demonstrating the utmost loyalty to his company.

Well, instead of the huge pat on the back and praise and accolades all round from work colleagues, I was really in trouble. My boss turned red with rage, then white with the fear of the repercussions for me breaking the law in such a manner. We buried the typewriter in amongst old stock, and the boss spent the rest of the day in hushed conversations with the secretary, fiddling with internal records and destroying invoices from Olympia to try and hide the fact that the typewriter ever even existed, let alone had been sold by us.

The police never arrived, the ex-typewriter “owner” never rang us (I suspect he would have known who took it, yet also knew it wasn’t paid for, and he had no intention to pay for it).

That day was a huge learning experience for me as a young typewriter technician, embarking on a career path that taught me a lot more than just how to fix typewriters.

Those early days for me, on looking back, were a bit like working for Arthur Daley of Minder fame. In a future submission, I’ll relate how we almost came close to being on the wrong side of the law in an equally hilarious experience.

↧

Christmas Typewriters #10

↧

The Short and Sporadic Life of Canadian Oliver Typewriters

ribbon spools on this Canadian-made Oliver No 3.

Canadian-made Olivers being used in Montreal in 1901.

Newark, Delaware, typewriter collector and historian Peter Weil got me thinking yesterday when he wrote "The manufacturer in these [1906 Oliver advertisements] is clearly listed as the Canadian Oliver Typewriter Company. Yet, there is the matter of Olivers made by the Linotype Company in Canada." Peter had sent me two advertisements, one of which was in French:

The ribbon spools of this Canadian-made model of the Oliver No 3 are horizontal.

Within a short time I was able to provide Peter with a definitive reply. The Canadian Oliver Typewriter Company and the [Canadian] Linotype Company were one and the same organisation, both originally based at 156 St Antonie Street, Montreal, and both controlled by the same man, John Redpath Dougall.

John Redpath Dougall (1841-1934), at one time owner of both the Canadian Oliver Typewriter Company and the Linotype Company and long-time editor of the Montreal Witness.

A full-page advertisement in the Winnipeg Tribune, July 27, 1904

The Linotype plant in Montreal a year before Dougall sold the company to Toronto in 1904.

Dougall founded the Linotype Company in Montreal 1891 and in 1898 expanded it to make variations of the Oliver No 2 and No 3 typewriters. The Canadian No 2 was a short-lived nickle-based $60 model sold by Montgomery Ward as a Woodstock. (Thomas Oliver was born in Woodstock, Ontario, and his typewriters were mostly manufactured in Woodstock, Illinois).

1898 advert

In May 1899, Dougall's Linotype Company also got involved in the "Battle of Detroit". A booklet containing "An Impartial Account of the Fierce War Waged in the Board of Education by the [Union] Typewriter Trust against the Oliver Typewriter, in the year 1899" was published by the Linotype Company of St Antoine Street. Perhaps, as the booklet was not published by Oliver itself, it may have been seen to be "impartial". However, it did include this fascinating passage: "This machine, the only typewriter outside the trust, having a free type bar, is the invention of Thomas Oliver, a Canadian, whose machine has been built in Woodstock, Illinois, for several years, the head office being in Chicago, and which is now being built by the Linotype Company, Montreal, for Canada and South America. This machine the Trust could not afford to buy on account of the revolutionary character of its construction, which would render all its present immense plant and most of its stock useless, and besides it is in the hands of a close corporation composed of wealthy business men, who understand just what they have got, and intend to hold it. Direct purchase being impossible, the trust’s only alternative was to resort to vilification and threats of patent infringements. This was the machine which entered the list against the trust machines at Detroit, and on January 10, 1899, the typewriter Waterloo was fought and won."

1899 advert

Above and below, 1900 adverts. Note the dig in the ad below at the "Typewriter Trust".

This image of a Canadian-made Oliver, serial number 1946, with vertically mounted ribbon spools, appeared on the front page ofETCetera No 4 in July 1988 (PDF here). It was at that time owned by Don Decker. Under the spare bar is a Canadian patent number and the words"by Linotype Company, Montreal".On the paper plate are the words "Canadian Oliver Typewriter Montreal". It has black keytops.

John Dougall senior

By 1901, Canadian Olivers were being described as the"only serious competition for US-made typewriters". They were promoted as being made from Canadian material by Canadian workmen, and as saving on duty.

Dougall was the son of Scottish-born merchant, journalist and publisher John Dougall (1808-1886), who in 1846 established the weekly the Montreal Witness. In 1871 the father left the Witness in the charge of his son and with support and capital from Manhattan residents moved to New York City, where he established the Daily Witness and the widely circulated New York Weekly Witness.

In 1903 John Redpath Dougall patented an improved Linotype machine, but under immense pressure from the Mergenthaler company's plans for international domination, he sold his Linotype Company to the Toronto Type Foundry in 1904. Upon doing this, Dougall reorganised his Montreal company as the Canadian Oliver Typewriter Company.1903 advert. Note the vertically mounted ribbon spools.

The Toronto Type Foundry's Linotype wing lasted only five years, until May 1909, when it was taken over by Mergenthaler as part of a $2.87 million worldwide expansion which valued the Toronto asset at $590,391. Mergenthaler also engulfed the Linotype and Machinery Company of Britain and Setzmaschinen-Fabrik of Germany. Mergenthaler claimed the takeovers were forced on it to "avoid litigation, consolidate patents and develop and improve the machine". Its own basic patents expired in September 1907 and it had failed to gain "territorial agreements" in Canada, Britain and Germany.

Mergenthaler's aggressive policies in trying to push into the Canadian market, through the Vancouver Daily Province newspaper, led to court action from the Toronto Type Foundry, in which the Ontario company claimed infringement of Dougall's patents and was represented by Dougall himself, in his capacity as a QC. Dougall's improved machine was said to be simpler and faster than the Mergenthaler, and cost half the price (at $1200 less).

1906 advert, courtesy of Peter Weil. Note the horizontal ribbon spools and the change of address for office and factory.

After the Canadian No 2 and No 3 Olivers were made from 1898-1903, the Linotype Company sold to Toronto in 1904, and the Canadian Oliver Typewriter Company reorganised, a new Canadian Oliver No 3, with horizontal ribbon spools, emerged. This was launched on the market in 1906. There are apparently only two Canadian Olivers known to exist in collections, the one with the vertically mounted ribbon spools being serial number 1946, and the other, with horizontal ribbon spools, serial number 2536, only differing from a US-made No 3 in decal wording.

After the death of Thomas Oliver in 1909, however, production of Canadian Olivers ended.

By 1912, the Canadian Oliver Typewriter Company's operations were entirely concentrated on nickel plating and polishing:

John Redpath Dougall

↧

Christmas Typewriters #11

↧

↧

Typewriter Oddities

An occasional potpourri of odd events relating to the typewriter.

Illustrator Blames Typewriters

For 'Mediocre' Books

In 1903, John French Sloan (1871-1951), the famous American magazine illustrator, blamed typewriters for "the publication of late years of so many mediocre books".

The Philadelphia Record said Sloan's claim was "novel and plausible". However, Sloan's reasoning was exceedingly convoluted. He said that before the typewriter, handwritten manuscripts of 100,000-150,000 words were not read carefully by editors in advance of publication. Typescripts were easily read, and "here and there, points of merit were found", leading to a decision to publish. "Eighty per cent more manuscripts are now read and 60 per cent more are now published," said Sloan.

Sloan, a realist painter and etcher, was one of the founders of the Ashcan school of American art. He is best known for his urban genre scenes and ability to capture the essence of neighbourhood life in New York City, often observed through his Chelsea studio window. He "embraced the principles of Socialism and placed his artistic talents at the service of those beliefs."

Interestingly, in 1908 Sloan drew this sketch, "The Picture Buyer", showing Remington typewriter company president, astute art collector and multi-millionaire Henry Harper Benedict inspecting a possible purchase.

Turks Ban Typewriters

In 1901, the Turkish Government announced its its customs department had decided to prohibit the entry of typewriters into the country. The decision was reached, it said, because there were "no characteristic about typewriting by which the authorship can be recognised - there is no distinct feature about it, as with handwriting, by which the person who used the machine can be traced". The Turks said they believed "anyone would be able to type seditious writings without fear of comprising himself".

The decision followed the arrival in Turkey of a consignment of 200 typewriters. The US embassy was trying to convince the authorities to "take a more reasonable attitude". Turkish customs were also preventing "hectographic paste and fluid" entering the country. The hectograph, or gelatin duplicator, was a printing process which involved the transfer of an original, prepared with special inks, to a pan or pad of gelatin. The hectograph was invented in Russia in 1869 by Mikhail Ivanovich Alisov.

Prism for Blind Typewriters

In 1888, a San Franciscan, Henry Otis Hooper (1823-94), patented a refracting-prism device to enable users of "blind typewriters" (Sholes & Glidden, Remington and Caligraph) to read what they were typing as they typed, without having to stop and lift the carriage. Although he was three years dead, Hooper got some publicity for his invention across the US in 1897 (New York Tribune, Sacramento Daily Union) and it continued to be publicised as late as 1905, 12 years afterFranz Xaver Wagner had perfected "visible" typing.

Typewriters 'Instruments of War'?

In 1917, at the height of World War I, the British Government's Solicitor-General tried to have 82 cases of US typewriters, intercepted on their way to Gothenburg in a Swedish ship, to be confiscated and condemned as "absolute contraband". The Solicitor-General said typewriters were "instruments of war". To support this view, he pointed out 4000 typewriters had been supplied to the British Army in France and that "no modern camp can be complete without typewrites". The court president responded, "What did Napoleon and Wellington do without typewriters?"

↧

Christmas Typewriters #12

↧

Bean's Corona 3 Portable Typewriter and the Bapaume Explosion

Australian soldiers clear debris after the explosion in the Town Hall in Bapaume on the night of 25-26 March 1917.

On a visit to Canberra today by Melbourne typewriter collector Diane Jones, we went to see the enlarged World War I sections of the Australian War Memorial. I was delighted to find that official war correspondent and war historian Charles Bean's Corona 3 portable typewriter is back on display, although now sans its tripod.

↧

Christmas Typewriters #13

↧

↧

Yes, Diane, there is a Typewriter Santa (and a Varityper, too)

Diane, your friends are wrong.

They have been affected by the scepticism of a sceptical age.

They do not believe except they see.

They think that nothing can be which is not comprehensible by their little minds.

- with apologies to Francis Pharcellus Church

Six days earlier, almost to the hour, I had been tempting the typewriter gods by scoffing at a suggestion in that morning's The Sydney Morning Herald, that in 1927 J.R.R.Tolkien (Lord of the Rings) had bought himself a "Varitype" typewriter. Happily, I saved myself a few blushes by checking and finding out that Wim Van Rompuy had a manual Varityper on his typewriter.be website.And then on Friday, the charming Melbourne typewriter collector Diane Jones and her partner Stephen Harrison breezed down my chimney, like a refreshing early Santa and his helper, and presented me with the conclusive evidence - a gift of my very own Varityper manual typewriter. (All this just a week after I had acquired a Varityper headline setter.)

In the case of Wim's machine, it is Folding model built according to Hammond patents. It is, in other words, pretty much a straightforward Hammond under another name

Later I recalled that Georg Sommeregger had come across a Varityper in Cologne almost exactly a month earlier. In the case of the Varityper Georg photographed, it has the pitch-switch on the side and the brittle Doler-Zink of Brooklyn castings, the same as mine. Except mine is set to toggling from 10- to 14-characters per inch, as opposed to 10 to 12-CPI.

There is also a pitch-switch on the Varityper from the Virtual Typewriter Collection of Enrico Morozzi, on the Typewriter Database.

The serial number on mine is 401585 9.

It was sold by Harrison & Flower of Birmingham in England:

The keyboard is really interesting:

This distinct variation of the Hammond, based on the 1916 Multiplex, was designed by Phelps, New York-born Arthur Stalker Wheeler (1869-) in 1922, toward the end of days for the Hammond company.

Following the death of James Bartlett Hammond in 1913, Neal Dow Becker (1883-1955) ran the company, which had been bequeathed by Hammond to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art (with the assets estimated as being worth $800,000). Becker tried valiantly to revitalise Hammond by restructuring and refinancing it in 1921, but things began to go downhill and in January 1922 the Corporation Trust Company was authorised to transfer its stock. Hammond was merged with the office supplies corporation, Kroy Typewriter, which had been established only weeks earlier.

Becker packed up and left in 1924. The end for the original company came with a devastating fire on June 23, 1926, which raged from 42nd to 90th streets in Manhattan and engulfed most of Yorkville and the East Side, including the Hammond factory on East 69th Street. The fire caused $500,000 in damage and stripped Hammond of much of its remaining assets.

Fred Hepburn's passport photo

What was left, notably patents, was acquired by civil engineer and investment banker Frederick Taylor Hepburn (1873-1956), who established the Varityper Corporation. Hepburn was a wealthy property owner and highly successful financial speculator who had special interests in Pennsylvania and Ohio power systems. Hepburn saw potential in the Hammond as an typesetting machine and had both manual (1927, with Wheeler's variable carriage feed mechanism) and an early electric version of the Varityper (1929, largely through Frank Harris Trego's designs) produced. He then sold out to Oakland-born Ralph Cramer Coxhead (1892-1951) and the electric model was extensively developed by first Trego (1873-1967) and then Charles W. Norton (1890-1952). The rest, as they say, is history.

By the time Hepburn died, his contribution to all this had long been forgotten. In fact, by 1935, the Hammond was already being described as a "relic" and an "antique typewriter".

Becker, meanwhile, went on to run Intertype (which developed the Vogue typeface) from 1926 until 1952.

↧

Christmas Typewriters #14

↧

Smith-Corona takes careful aim and shoots itself in the foot

"Let your voice do the writing ..."? Isn't that what a typewriter is for?

Certainly, one of the main reasons one might buy a Smith-Corona typewriter today would be to write a letter.

So why was SCM shooting itself in the foot in 1967?

I readily confess I'd paid little heed to one of the items being flogged in the 1967 SCM Christmas advertisement I posted a couple of days ago. I just looked at the typewriters (OK - and the ladies in pyjamas).

That is, until comments to the post from Ted Munk and Tina Martin made me go back and take a closer look.

Ted wrote, "Yeah, now I want an SCM 'Mail Call'. I wonder what media it used? Knowing SCM, probably some weird, proprietary tape cassette." Tina added, "That Mail Call gizmo is interesting."

The "gizmo" was the Smith-Corona Letterpack Mail Call - a PlayTape battery-powered audio cassette player on a two-track format. A distant forerunner of voicemail, it allowed users to record messages on small cartridges and mail them to anyone with a matching device. Smith-Corona promoted the system as being "a more personal alternative to writing a letter". The two-unit starter kit cost close to $70.

The PlayTape format was soon superseded by the 4-track and 8-track formats and SCM went back to concentrating on typewriters.

The short-lived SCM Mail Call device was the work of Frank Stanton (1920-1999), who developed a compact 2-track system while in the US Navy during World War II. PlayTape was successfully launched at an MGM Records distributor meeting in New York in mid-1966. Apart from MGM, the players were also sold by Sears.

Stanton then introduced a special dictating device aimed at the business market, which he envisioned as a replacement for written memos and letters. His idea was marketed to SCM. While the music market for his players enjoyed limited success, the business side never took hold.

Certainly, one of the main reasons one might buy a Smith-Corona typewriter today would be to write a letter.

So why was SCM shooting itself in the foot in 1967?

I readily confess I'd paid little heed to one of the items being flogged in the 1967 SCM Christmas advertisement I posted a couple of days ago. I just looked at the typewriters (OK - and the ladies in pyjamas).

That is, until comments to the post from Ted Munk and Tina Martin made me go back and take a closer look.

Ted wrote, "Yeah, now I want an SCM 'Mail Call'. I wonder what media it used? Knowing SCM, probably some weird, proprietary tape cassette." Tina added, "That Mail Call gizmo is interesting."

The "gizmo" was the Smith-Corona Letterpack Mail Call - a PlayTape battery-powered audio cassette player on a two-track format. A distant forerunner of voicemail, it allowed users to record messages on small cartridges and mail them to anyone with a matching device. Smith-Corona promoted the system as being "a more personal alternative to writing a letter". The two-unit starter kit cost close to $70.

The PlayTape format was soon superseded by the 4-track and 8-track formats and SCM went back to concentrating on typewriters.

The short-lived SCM Mail Call device was the work of Frank Stanton (1920-1999), who developed a compact 2-track system while in the US Navy during World War II. PlayTape was successfully launched at an MGM Records distributor meeting in New York in mid-1966. Apart from MGM, the players were also sold by Sears.

Stanton then introduced a special dictating device aimed at the business market, which he envisioned as a replacement for written memos and letters. His idea was marketed to SCM. While the music market for his players enjoyed limited success, the business side never took hold.

When Stanton (born November 30, 1920) died at his home in Water Mill, Long Island, on May 9, 1999, aged 78, he was remembered in a New York Times obituary for being an entrepreneur and real estate investor who developed an early videocassette. His company, World Wide Holdings, was established for trading in surplus goods left scattered around the world in the aftermath of World War II. With a foothold in North Africa, the company became the largest importer of sugar into Morocco. It was later involved in importing Volkswagens, Porsches and Audis into the United States. Later, the company engaged in toy manufacturing and movie distribution. In the late 1960s, World Wide Holdings joined forces with the Avco Corporation, a high-technology manufacturer, to found Cartridge Television, a company that produced a videocassette and player (Cartrivision) which anticipated later developments in the field. In the 1970s, World Wide Holdings branched into real estate.

His obituary failed to acknowledge his pioneering work in the field of consumer audio systems. In the US, Volkswagen was the only car manufacturer to offer a PlayTape player as optional equipment. The Volkswagen Sapphire I OEM model was designed for in-dash installation, and included an AM radio. The Sapphire II aftermarket version omitted the radio, and was designed to hang off the dashboard.

↧

Christmas Typewriters #15

↧

↧

Colour My (Typewriter) World

The latest edition of Vanity Fair to reach the magazine stands (in Australia at least) marks a welcome return to images of typewriters in this esteemed journal - and such images appear in relative abundance. I had waited impatiently for some time for typewriters to return in the monthly, and perhaps the November edition reflects some sort of a "catch-up". Well, it won me back. While enduring the barren period, I had felt disappointed in editor Graydon Carter, for his apparent failure to insist that each issue must contain a minimum of one or two typewriter images. After all, his own name appears under a typewriter on the masthead:

Previously, Vanity Fair had proved not just a fairly rich source of typewriter-and-writer images, but also in small but significant ways had contributed to our knowledge of typewriter history (Hemingway's Corona 3, as one example). One notable black spot was a set-up photograph to illustrate a story about screenwriters in Hollywood in its heyday - a plastic East German-made Robotron was used as the prop. Ugh!!!

Front and centre (well, almost; OK, slightly to the left of centre) of a double-page colour image used in this latest Vanity Fair, to introduce a feature ("Innocents on Broadway") on the 1944 musical On The Town, is a deep green Hermes Baby portable typewriter.

Yes, folks, this most definitely started out in life as a black-and-white photograph, one taken by Californian Bob Willoughby, "the man who virtually invented the photojournalistic motion picture still". Strictly speaking, the image doesn't relate directly to On The Town, but was taken 10 years after that musical's launch on Broadway. Willoughby snapped the shot in 1954 in Los Angeles, while Adolph Green and Betty Comden were working on Peter Pan. Rights to the Willoughby photos are now owned by MPTV, as can be gleaned from the watermarks on the original prints:

Quite why Vanity Fair felt the need to run a colourised version I cannot say. However, the magazine does give credit to the colourisation process to one Lorna Clark - albeit in tiny 2-point type, alongside acknowledgement of Willoughby and MPTV.

Now, let me be the first to admit that I believe the colourisation of old black-and-white photos, and film, is a fine skill, a process which can produce some interesting results. There is clearly a risk involved, however, in getting the colours right. My strong feeling is that Ms Clark didn't get the Hermes Baby right. My guess would be that the portable typewriter sitting on the floor of the LA home of Green and Comden in 1954 was grey. But, it seems, the floor tiles are black and grey, so ...

There is another colourisation of a photo of Comden at a typewriter - this time a Royal portable - further into the Vanity Fair feature article. This time, the 1944 shot shows Comden sitting on the floor typing beside choreographer Jerome Robbins, with On The Town composer Leonard Bernstein and Green on a couch in the background:

Here is the original black-and-white image:

OK, so I'm a Luddite stuck in the Dark Ages, but I do happen to prefer my typewriter-related images to be published as originally processed, be it black-and-white, sepia-coloured (I do like sepia) or whatever. Art for art's sake and all that.

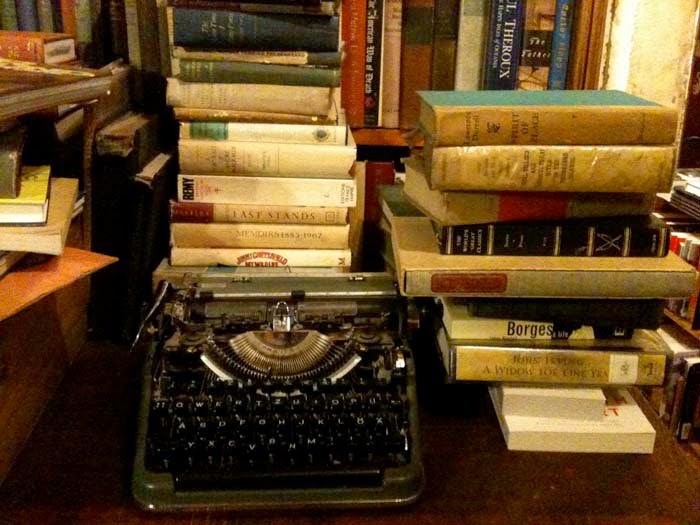

As for other typewriter images in this particular edition of Vanity Fair, they are contained in a feature ("In a Bookstore in Paris") about the Shakespeare and Company's George Whitman and his daughter Sylvia. George Whitman (seen below, 1913-2011) "took up Sylvia Beach's mantle" by opening this present-day store in 1951.

Sylvia Beach Whitman (1981-) continues to run the store. In it remains at least one portable typewriter, an Olympia SM3 without its ribbon spools cover.

Happily, Vanity Fair includes in this feature a black-and-white image of writers at the store, taken in the 1950s, in uncolourised form. It shows Richard Wright, his wife Ellen, George Whitman and American authors Max Steele and Peter Matthiessen, with what appears to be an Olivetti Studio 44 on a desk, between Steele and Matthiessen.

Note: Only three of the typewriter-related images from the Shakespeare and Company bookstore, shown above, appear in November's Vanity Fair.

↧

Our Fractured World

↧

Christmas Typewiters #16

↧

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)