With the GOP in turmoil, it's timely to look at one of the Republican Party's Californian founders, and his involvement with the first machine called a Type-Writer ...

Oakland, California "capitalist" Charles Ames Washburn."That it can be made vastly superior to Sholes' machine is now palpable and admitted by all who have studied it. Of one thing I am very confident - that is, I can run Sholes' machine out of the market." - Charles Ames Washburn, October 1875.

'That' is the 'Typeograph', which was never made.

All typewriter lovers know who Sholes and Glidden were - the men behind the Sholes & Glidden typewriter (though they may not know how Carlos Glidden came to be included in the name of Christopher Latham Sholes' marvellous invention). And many will also know of Jefferson Moody Clough, the experienced Remington engineer who prepared the Sholes & Glidden for mass production at the E.Remington & Sons plant at Ilion, New York, in 1873-74.But Charles Ames Washburn? What was his contribution to this epoch-making machine? The answer to that question may be difficult to find in typewriter histories (the more so because the theories that are online are incorrect*). Still, Washburn's input was sufficiently significant for the following breakdown of agreed royalty payments on each of the 400 Sholes & Gliddens sold in the United States between July 1 and December 31, 1874 - at $125 a pop:$1 to C.L.Sholes.

$1 to C.Glidden.

$1 to C.A.Washburn.

50 cents to J.M.Clough.

Yes, a mere $3.50 in royalties out of each $125 sale. But the $3.50 was to be paid from just $12 a machine which flowed through to the Type-Writer Company from Remington. In 1875 Remington agreed to take over sales and to pay the Type-Writer Company $15 a machine for patents rights, but deducted $3 a machine for debts owed to it by Yost.

And Washburn was to receive the same amount as Sholes and Glidden. Sholes was only entitled to $1 because by the time the Sholes & Glidden went into production, he had already sold two portions of his three-tenths share in the enterprise. As well, James and Amos Densmore and George Washington Newton Yost, acting as Densmore, Yost & Company, had acquired almost all of Sholes' (and Glidden's and Samuel Willard Soulé's) patent rights on the machine, along with the two-tenths share in the overall project that Sholes had sold.

Sholes' original three-tenths ownership was settled in the "agreement of trust" drawn up by James Densmore on November 16, 1872. Densmore had originally held four-tenths, while Glidden's wife, Phebe Jane ("Jennie") Glidden, and Densmore's brothers, Amos and Emmett, all held one-tenth each. Densmore, Yost & Company had bought Emmett's stake in US patents, though Emmett undeservedly retained control over all "foreign" (that is, British) patent rights. Emmett claimed $700 a month in royalties for British sales, but this ludicrous amount of money was not paid.

Milwaukee lawyer Carlos Glidden. His wife pushed hard for his "fair share".

Glidden got $1 because, apart from his wife's one-tenth share, the couple also claimed to be entitled to one-tenth of all of James Densmore's profits from typewriter sales, according to their interpretation of the wording of the "agreement of trust". Upon re-reading the document, Densmore had had to concede the Gliddens "had him" (that is, "over a barrel"). (Glidden got his name on the machine when Densmore was forced to placate him after Scientific American, on August 10, 1872, had attributed the invention solely to Sholes. Densmore and Sholes had earlier agreed the machine would be called the Sholes & Densmore, and the machine's leading historian, Richard Current, believed that by rights that should have remained the case.)

Clough received 50 cents for his work in getting the Sholes & Glidden ready to go into production at E.Remington & Sons. He had also lent James Densmore $3000 in Ilion in early March 1873, just after Densmore and Yost had signed a contract with Remington to make the typewriter. This money was meant to assist Densmore and Yost in setting up a business to sell the Sholes & Glidden.

So why was Washburn entitled to $1? Well, after Remington had signed the production contract, it found Sholes' designs infringed a patent (No 109,161) issued to Washburn on November 8, 1870. Though Sholes'"axle" machine was developed in 1869, it was not patented until August 29, 1871, more than nine months after Washburn's patent. Because the Type-Writer Company still held the patents rights, Remington ensured that under the terms of its re-drafted contract, Densmore and Yost were obligated to pay this royalty to Washburn, not the manufacturer.

It is very interesting that Washburn used the title "type writing machine" in 1870. Densmore claimed "type-writer" was the name he gave Sholes' invention - and Richard Current suggests this was some time after 1867. But "type writing machine" had been first used by Scientific American on July 6, 1867, to describe John Pratt's "Pterotype".

Washburn's patent specifications outlined the one particular element which was infringed by Sholes' longitudinal platen movement:

*Other sources, such as Wikipedia, incorrectly claim the relevant device was the hinged carriage. Regardless of the inaccuracy of this claim, it would seem to me that so simple a thing as a hinged carriage would hardly qualify as a patent infringement, anyway, but the design of the mechanism for moving the carriage longitudinally would most definitely be an infringement. In fairness, Sholes was unaware of the Washburn design in 1869-70.

On December 28, 1874, Amos and Emmett Densmore had incorporated "The Type-Writer Company", with capital stock valued at $250,000, divided into 2500 shares of $100 each - James Densmore and Yost held 1000 each and Amos Densmore 500. The Type-Writer Company immediately granted Yost and English-born Edward Denning Luxton (1830-1901) its contract with Remington to have made and to sell typewriters, under the company name Densmore, Yost & Company, General Agents.

The Type-Writer Company soon fell behind with royalty payments and in mid-1875 it was sued byWashburn for monies owed to him. Washburn also warned that he would induce Samuel Colt's Colt's Patent Fires Arms Manufacturing Company to manufacture the Washburn typewriter (the "Typeograph") in Hartford, Connecticut. In two letters to his brother Cadwallader Colden Washburn (who had been Wisconsin Governor from 1872-74), dated October 6 and 19, 1875, Washburn used a prototype of his machine to type in neat if chilling words: "That it can be made vastly superior to Sholes' machine is now palpable and admitted by all who have studied it. Of one thing I am very confident - that is, I can run Sholes' machines out of the market."

It is interesting that both Sholes and Washburn were politically active Republicans, but there any link between the two men ends. While Sholes was an honest, modest, mild-mannered and patient gentleman, described by friends as "retiring", Washburn became a pushy go-getter, a firebrand, described by Abraham Lincoln as "temperamentally unstable" and by his own brothers as a rapscallion, a marplot and as downright dishonest. One political opponent called him in print a "dirty dog".

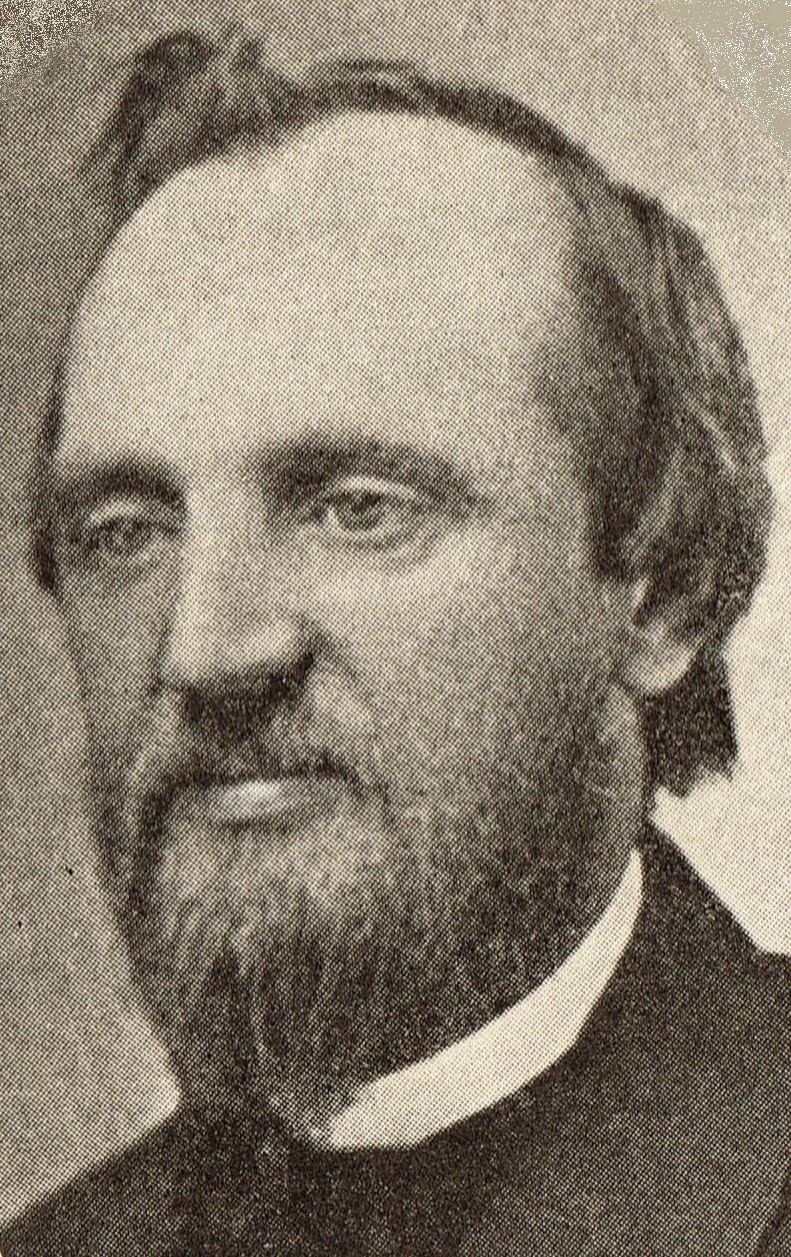

Yet, for all that, Charles Ames Washburn (above) was one interesting man, albeit one totally neglected in typewriter histories. A brief summary of his life follows: .He was born in Livermore, Maine, on March 16, 1822. Four of his brothers (Israel Washburn Jr, 1813-83; Elihu Benjamin Washburn, 1816-87; Cadwallader Colden Washburn, 1818-82; and William Drew Washburn, 1831-1912) became United States Congressmen - one of them, Israel Washburn Jr, was the founder of the Republican Party. The Washburn brothers were cousins of Dorilus Morrison, first mayor of Minneapolis. Israel Jr

Elihu

Cadwallader

William

Morrison

.Charles attended Wesleyan Seminary at Kents Hill and graduated from Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Maine, in 1848..He taught the children of rich cotton merchants in Mississippi and Louisiana. He then worked for the Land Office in Washington before moving to Wisconsin.

.He became a lawyer in Mineral Point, Wisconsin.

.In 1849 he followed the gold rush to Mariposa, California, first panning in the mines, then becoming a book seller. He later walked from Mariposa to San Jose, finally settling in Oakland.

.He was the editor of Californian newspapers the Sonora Herald (1852), the Daily Alta California (1854), the Evening Journal (1855), the Star of the Empire (1856) and the Daily Times (1858-60). Charles co-owned the last named newspaper with Alvan Flanders (below). .In 1854 Charles, following his brother Israel's move in Washington, helped organise the Republican Party in California. .Also in 1854, Charles was seriously wounded in a duel in San Francisco with fellow editor Benjamin Franklin Washington, using rifles at 40 paces. Charles came to believe the duel cost him his chance to follow his brothers into congress, at the 1858 Californian Republican Convention..By 1859 he had become close to Californian Democratic Senator David Colbreth Broderick, who he admired and strongly supported through his editorials. This friendship led to Lincoln considering Charles to have "unsound party loyalty" and to be of "unstable temperament". Charles wrote passionately about Broderick's death in a duel with chief justice David Smith Terry. Broderick

Killer: Terry

.In mid-August 1860 Charles became seriously ill and in April 1861 he was replaced as editor of the Daily Times. He was made President Elector for California. He went to Washington seeking an appointment from Lincoln.

.Despite being thought "disloyal" and "unstable" by the president, but perhaps to get him out of the country, Charles was appointed by Lincoln as Diplomatic Commissioner to Paraguay in mid-1861. His brother Elihu and Lincoln were close.

. Charles returned Paraguay in 1863-68 as United States Minister Resident. Apparently he had to be rescued by a gunboat. Wedding portrait of Charles Washburn and his wife Sallie Catherine Cleaveland, whom he married in New York on May 11, 1865.

.In 1861 Washburn wrote a thinly veiled fictional autobiography called Philip Thaxter (he was the character of "Ben") and in 1865 a fictional "family history" called Gomery of Montgomery. In the 1870s and 80s, he produced other, more serious works:

In his younger days, Washburn believed himself to be a "signal failure", a dreamer who lacked skills. Even after moving to California, he was thought of as "liable to be imposed upon by shrewd business types, a mere child in the commercial environment".

Whether it was the gold fields in the late 1840s, the rough and tumble world of newspapers in San Francisco in the 1850s, or his experiences in trying to deal with Francisco Solano López in Paraguay in the early 1860s, but as Washburn grew older he became increasingly ambitious for fame and fortune, his business dealings more cut-throat.

These traits were evident in Washburn's involvement with Sholes, James Densmore, Yost and the Remingtons in 1873-74. At the time of this imbroglio, Washburn was describing himself as a San Francisco "capitalist" and living at 302 Montgomery Street, Oakland. He subsequently invented a register for train and tram passengers. Washburn died in New York City on January 26, 1889, aged 66.

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)